We're all schedulers now

From Radio Times to Screen Time: how EPGs are teaching us to manage our attention.

We’ve been running some workshops for clients at Storythings in the last few weeks, and I’ve found myself repeatedly saying something that’s been running around my head for a while - we’re all schedulers now.

The first phase of internet adoption was focused around the search engine, and the skill it taught us all was, broadly, how to be a librarian or researcher. Before the early 90s, most of us didn’t spend part of our day writing queries for databases and then evaluating and refining the results. But when we learnt to open a browser and type into a search box, that is exactly what we were doing. We’re all researchers now.

Something else has happened in the last 10 years, something that has given us another unexpected skill. After learning how to become researchers, we’ve all had to learn how to become schedulers. As smart phones and smart TVs have introduced streaming media and VOD services, we’ve had to learn how to manage our attention in ways that are incredibly sophisticated. The combination of these new skills, and the products we use to do it, are going to have a profound effect on culture and society in the next few decades, just as the rise of the browser and search engine did in the early 2000s.

I was thinking about this over the last few weeks as I analysed OFCOM data from their recent Media Nations 2020 report. Since the rise of internet adoption in the 2000s, live broadcast TV viewing has been dropping as a proportion of overall video viewing, but it’s always been above 50%. In the last six months, this has changed. Here’s the stats for 2019, when Live TV represented over 53% of video viewing:

And here’s the stats for April 2020, just after the COVID lockdown:

The interesting thing to note first of all is the huge rise in total video - 6 hrs 25 minutes in April 2019, more than 1.5 hours more than the average for 2020. April was unseasonably warm in the UK, but of course, we were on COVID lockdown, so were limited to 30 mins exercise outside a day. It looks like we spent that extra time watching video, but the big winner was SVOD services, which almost doubled from 34 minutes a day to 71 mins, whilst Live TV only added 24 mins, a 15.5% increase. This meant that for the first time, Live TV was less than 50% of our total video consumption.

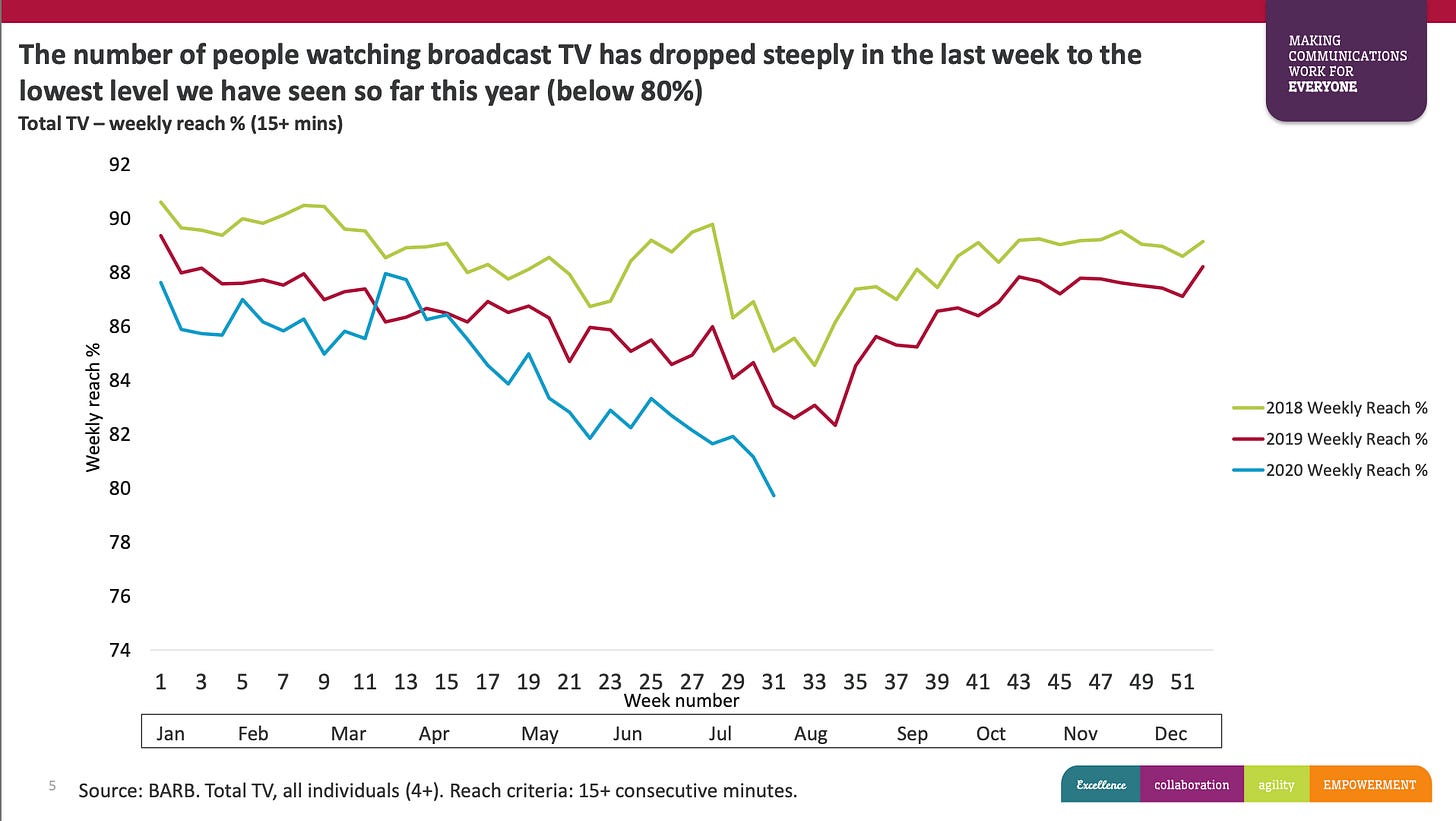

But since then, it’s dropped even more. Weekly reach, measured as the number of UK individuals watching at least 15 minutes of broadcast TV, dropped to just below 80% of the UK population.

If we look at the figures for average minutes of Broadcast TV watched, you can see that 2020 briefly bucked the annual trend of decline as COVID hit, but is now dropping sharply to match the decline seen in 2019. Since 2014, average daily minutes viewing of broadcast TV has dropped year on year, losing around 45 mins a day over that period:

Why is this so important? Because we’re all watching way more video than ever before, but we’re watching it in different ways. We might be in the last decade of a cultural invention that has dominated media for the last century - the schedule.

I’m a bit obsessed with the schedule, as you’ll know if you’ve ever seen me talk at an event. It is a cultural construct that was invented at the turn of the 20th century as entrepreneurs working with new telephone networks imagined they might become a broadcast medium, and launched subscription content services piped to one-way phones installed in people’s homes. This gave them an interesting problem - how do you organise a programme of content when there are no physical limitations to how long you could keep something going? Their answer was to tie the lengths of their programming to the hours of the clock, and the broadcast schedule was born.

I think the broadcast schedule was one of the most culturally influential inventions of the 20th century. Although telephones didn’t end up as broadcast devices, radio soon came along, and then TV, both of them copying the schedule as a way of organising their content, and their audience’s attention. I’d argue that the power of the broadcast schedule (and the regulation of it by governments) created public spaces that deeply influenced the kind of politics, and progressive ideas, that affected society in the second half of the twentieth century. It’s only now, as the schedule is losing influence to algorithmic social streams like Facebook, that we can recognise exactly how influential the schedule has been on society.

When I worked at the BBC and Channel 4 in the late 2000s, I was surprised to find that the most powerful people in the organisation was not the talent or senior execs, but the schedulers. These people understood the dark arts of audience attention, and made decisions that could make or break a TV show, by running it against a competitor’s big hit, or pushing it backwards by an hour to a late-night slot. When audiences had little control over how to watch a show, the schedule, and the schedulers, were the hit-makers.

But now the power has shifted, and responsibility for managing our daily media attention has moved to algorithms and, well, us. We used to look at the Radio Times to see what was scheduled for our attention, but now we look at Screen Time to see how much attention we’ve given to our glowing glass rectangles. The really big trend of the last 10-15 years is just how much more of the day we now spend consuming media. This trend of how we spend our attention has been tipping towards digital for a while, but COVID seems to have been the watershed moment, and if lockdowns continue to curtail our behaviour for another six to twelve months at least, these new behaviours will only become more deeply embedded.

So right now, I’m fascinated with how we all manage our increased video watching habits, and how products have been developed to help, or hinder our efforts. I’ve written and talked a lot about algorithmic streams as a new cultural concept that will be as influential in the 21st Century as the schedule was in the 20th. Social streams have had a incredible effect on society and culture in the last decade, and they will continue to shape the next few decades. But something else has happened as well.

Alongside scrolling through social streams, we’ve also been binging through on-demand services. There is a whole series of design patterns around this behaviour that are nowhere near as well studied as Facebook and Twitter. This might be because they look, on the surface, quite familiar. Social streams were a radical departure for how we consumed content, atomising traditional structures like newspapers and magazines, and rearranging them in real time according to algorithms fed on data about our emotional responses. By comparison the electronic programme guides (EPGs) of VOD services like Netflix or Amazon are, at first look, a little like digital versions of the TV listings or Blockbuster video stores shelves we used to browse through in the 1980s and 1990s.

If the social stream has been optimised to give us an answer to the question ‘What’s happening now?’ (or more realistically - ‘What people are getting angry about now?’) then the EPG is being optimised to answer a more personal, less real-time question - “What shall I watch (or listen to) next?”

There are a couple of small, but important innovations in EPG/VOD design. I worked on the design of the first iteration of iPlayer at the BBC back in 2006, and the biggest problem we had was how to manage the egos of the different channel controllers on the iPlayer homepage. There was hardly any data collection in the product at that point, so algorithmic personalisation wasn’t really possible.

But there are other innovations outside of the algorithm. The first, started initially by Youtube before adoption by Netflix and all the VOD is auto-playing the next episode. This gets to the heart of the fundamental question we ask ourselves when we are self-scheduling our media - what should I watch next? This is solved for us in social streams, and YouTube, by an never ending scrolling list of new content, but social streams don’t seem to work in the living room in quite the same way. We seem to want to make more intentional decisions when we spend longer patterns of attention on video content, and social streams just don’t seem to work. Instead, auto-plays encourage us in one of the most important new behaviours we’ve learnt in the last few decades - binging. Binge viewing (or listening in the case of podcasts) has been one of the most important new behaviours in media, one that just would not have been possible in a world dominated by live scheduled TV.

The second interesting design feature is niche categories. Netflix has over 3,000 category codes in its EPG, each one representing a particular niche content area. These are mainly used as tags on content listings, but they’re a fascinating insight into how deep Netflix goes in cataloguing of niche content interests. For example, category code 1721544 represents Canadian Christmas, Children & Family Films; whilst 1133133 is for Turkish movies. This feels like a marriage of something like the Dewey Decimal System and the Folksonomies that emerged on early blogging and photo sharing sites like Flickr. Part of the skill of understanding what we might want to watch next is the ability to recognise patterns, and these deeply niche category codes feel like a really important part of how Netflix recognises patterns. They’re like Facebook advertising target groups, but not nearly as creepy. I don’t think they’re ever going to be a big part of the actual interface of an EPG for the user, but they’re a vital heuristic if you’re trying to train an algorithm. Netflix’s marketing is similarly aligned with specific niches and communities, with social channels like Strong Back Lead, Con Todo and Netflix Family.

The third interesting design feature is something that has caused a lot of controversy in social streams - trending charts. On Twitter and Facebook, trending topics are a kind of snapshot of society’s id - a crazed and manic combination of breaking news, celebrities and memes that feels like it’s being shouted into the sky, accompanied by a crowd with pitchforks at the ready. Netflix has only recently added a trending shows interface, and intriguingly, they show it as a top 10 chart. The chart, as a way of organising content according to it’s current popularity, was invented by the music industry in the 1950s, but has waned in influence in recent years as music listening moved to streaming services. Reimagined by Netflix, it acts as a useful window into what everyone else is watching at the moment. It doesn’t feel as real-time as trending topics, but instead gives a feeling of currency and shared experience that used to be the experience of watching scheduled TV. The trending chart is a little window into what everyone else is watching - a small watercooler moment into the wider Netflix audience’s behaviours.

None of these design elements is outrageously complex or innovative. In fact, compared to the relentless product innovation of social stream platforms, VOD EPGs feel like they are relatively stately in their development. But this is why they’re fascinating to me. They’re reinventing another part of our public realm - as the stream reinvented newspapers and magazines, VOD EPGs are reinventing TV channels and schedules. We need to be interrogating the design choices the streaming platforms are making, and asking ourselves whether they are creating opportunities for us to binge on diverse new story worlds that open up the world to us, or whether they are focusing us, like social streams, into ever more limited filter bubbles.