Introducing Mr X

60 years ago, The Beatles made ratings history with first appearance on US television. A few hours later, on the same channel, the man who invented ratings made his first, and only, TV appearance.

I started this newsletter to share research about the history of audience attention metrics for a book about the life of Arthur C Nielsen Sr & Jr, the founders and directors of the Nielsen company and inventors of TV ratings technology. During this research, I found out a remarkable coincidence - one of the highest rating TV shows of all time was the same night as the only TV appearance of Arthur C Nielsen Jr, on the show What’s My Line?

I’m not sure if the book will be published now, so I thought I’d start sharing chapters on this newsletter instead. This is the first chapter, about that night exactly 60 years ago when The Beatles and Nielsen Jr both appeared on tv within a few hours of each other.

BTW- if you’ve subscribed to this newsletter for insights about audience attention, I now do more writing about that on our Storythings newsletter Attention Matters. I’m going to use this newsletter to post chapters and insights from the book, so if you love really niche research into the history of attention metrics, stay here! If not, you might want to unsubscribe from this newsletter and join Attention Matters instead:

Introducing Mr X

It’s 8pm, February 16th, 1964, and something momentous is about to happen. In living rooms across America, a newly familiar ritual is being carried out, as dinner is cleared away and families gather around the television. In the last decade, the number of TV sets in America has doubled, and fifty-one million of them are being switched on, vacuum tubes warming up, fuzzy black and white pictures coming into focus. Like almost half of America - and pretty much every teenager - you’re in your living room, tuning the TV to CBS for The Ed Sullivan Show.

The show opens with the sights and sounds of a horse race, crowds cheering as the horses cross the line, the camera cutting to a long shot of the finish as the show titles are superimposed over the top.

“Good Evening Ladies and Gentleman! Tonight, live from Miami Beach, the Ed Sullivan Show! Tonight the show is brought to you by Lipton Tea, your change of pace drink. Your change of pace and flavour of refreshment. Brisk Lipton Tea.”

This is not what you’re waiting expectantly to watch. You’re not sitting there - butterflies in your stomach, curled in a knot on the sofa or fidgeting on the floor - waiting to hear about Lipton Tea.

“And now from the stage of the Deauville Hotel, here he is, Ed Sullivan!”

The picture cuts to a long shot over the heads of a restless looking crowd. In the distance you can see the stage, thick drape curtains, various figures moving cameras and equipment. Cut to Ed Sullivan in a sharp suit and pocket square, slicked-back hair in a widow’s peak, hunched shoulders and his long, hang-dog expression. “Thank you very very much, thank you” he says, arms coming out to still the crowd’s applause.

“Well you know, it’s so very nice to be here, thank you Ralph Renick for that nice intro. And now, this has happened again. Last Sunday, on our show in New York, The Beatles played to the greatest TV audience that’s ever been assembled in the history of American TV. Now tonight - here in Miami Beach - again The Beatles face our record-busting audience. Now before I bring on The Beatles, lets… quiet!”

Sullivan holds out his hands again. He was stiff and unbending for this first monologue, arms tight by his side, shoulders bouncing up and down like a marionette. Now, as he barks ‘quiet!’ he holds his arms out wider and smiles, the crowd takes the cue and laughs nervously, and he visibly relaxes.

“Let me tell you the weather here is sensational, even our Californian friend George Fenneman agrees with me”

He draws out the last syllable in ‘agrees’ and slides off camera to the left as George Fenneman steps in to audience applause. He looks exactly the same as Sullivan - sharp suit, slicked-back hair, widow’s peak.

“I certainly do Ed. Yes, it’s always pleasant working here in Florida, the people are really great. Now, for instance, let me show what happened today, out at the pool.”

The picture fades and opens up on an establishing shot of the Deauville Hotel, then cuts to a close up of George Fenneman by the pool, a box of Lipton Tea placed on the table in front of him.

The show has been on two minutes already, and we’re still watching Fenneman by the pool, still in a sharp suit, but seersucker instead of dark wool. It seems to go on for ages. Then - finally! - it cuts back to Fenneman on stage. After a last plug and show of the Lipton Tea box, he hands over: “And now, Ed Sullivan.”

You can hear the crowd again, restless like you, applauding with the odd scream or squeal in the background. There are hums and noises coming from behind the curtains, sounds of amps and instruments being plugged in. Ed Sullivan comes in again from the left, shakes Fenneman’s hand and looks at the camera. He doesn’t look hunched up now, but is smiling, full of energy, his body swaying as he talks.

“Ladies and Gentleman”

A pause, a long look down the camera.

“Here are four of the nicest youngsters we’ve ever had on our stage, THE BEATLES - bring em on now!”

As he says their name, screams erupt from the crowd, and Sullivan throws his right arm across his body, spinning around like a pitcher delivering a fastball, all his nervous energy exploding until he ends up with his back to the camera, eyes looking back to where he’d just entered, as if he has to shield himself from what is about to happen.

Finally, three long, tortuous minutes into the show - there they are. Paul, George and John burst forward to take their mikes, George hitting a bass note on his guitar as the curtains part, Ringo smiling from behind the drum kit. Paul looks back at Ringo, and shouts ’1,2!’ There’s a rumble of drums, clanging guitar chords and three voices in close harmony:

“She Loves You Yeah, Yeah, Yeah!”

Live, from Miami, into over fifty million living rooms across America, come The Beatles. The cameras in the Deauville Hotel beam out their signals to New York, Colorado, Michigan, Kentucky; picked up by aerials fixed to suburban rooftops, or wires propped on bookcases. Fifty million vacuum tubes, framed in ornate wooden surrounds, trace the images of four young men from Liverpool onto domed glass screens.

Their shiny grey suits are a contrast to the sober uniforms of Ed Sullivan and George Fenneman; tighter fitting, with contrasting dark collars. Despite it all appearing in black and white, they seem like a flash of colour, all shaking mop hair and jerking guitars. Sometimes, in close-ups, the primitive technology can’t cope with the contrast between them and the stage behind, and they are ringed in a halo of dark shadow, as if they were cut out from their surroundings.

During the third song - All My Loving - Paul sings the line “I’ll pretend that I’m kissing, the lips I am missing, and hope that my dreams will come true” and as the shot closes in on him, he looks straight down the lens, through the cameras, across the air, down the aerial, into the vacuum tube, onto the domed glass - and straight at you.

The Beatles have been dominating radio stations since late 1963, forcing Capitol to release their album earlier than planned, but what America wanted was not just to hear them, but to see them.

And now they’re here, in your living room, as they play to a packed ballroom in Miami. And you’re part of it, part of the biggest TV audience America has ever seen, over 70 million people in 50 million homes, all watching at the same time. Only television could create the illusion that The Beatles were in your living room, and Paul McCartney was looking straight into your eyes.

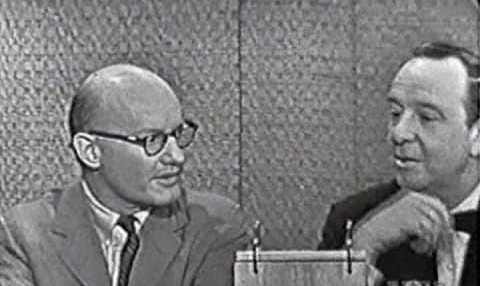

A few hours later, back in New York, a man twice the age of The Beatles is about to appear on another CBS TV show. He too is dressed in a grey suit, but not the same tight-fitting cut as The Beatles, and without their dandy contrast collars. Instead of a mop top haircut, he is completely bald, with small round wireframe glasses.

The show is filmed in CBS Studio 52, just around the corner from the more impressive Studio 50 where The Ed Sullivan Show is usually recorded. Just seven days earlier, Studio 50 had been the location for The Beatles’ first US TV appearance.

Studio 52 is more modest, a converted musical theatre adapted for TV and radio game shows. At 10pm, a light jazz theme tune plays over the cartoon intro to What’s My Line?

The four hosts - Dorothy Kilgallen, comedian Buddy Hackett, talk show host Arlene Francis and Bennet Cerf, the founder of publisher Randon House - take it in turns to introduce each other and take their seats. Cerf is last, and finishes by introducing their host.

“And now it’s my pleasure to introduce our panel moderator, who causes riots wherever he goes - and remember all you beautiful little girls in the audience you promised me you wouldn’t go into hysterics when I introduced him - John Charles Daly!”

The joke is a callback to The Beatles TV appearance around the corner in Studio 50 a week ago, and then again, just a few hours earlier that night, in Miami. The audience laugh, and then dutifully scream as Cerf waves his hands in mock astonishment. The laughter continues as Daly comes on stage and takes his seat behind the desk across from the panel. Like the other two men, he’s in a sober black suit with bow tie.

The contrast between the five people now on stage in Studio 52 and the four men who just appeared in Miami could not be greater. The shock and impact of The Beatles’ second US TV appearance has caused ripples through the rest of television, so even a show as tightly formatted as What’s My Line? - now in it’s fourteenth year - has to find a way to acknowledge it. But Daly soon settles the show into a familiar routine, gently chastising Cerf for his intro, and sharing a small bit of repartee with Hackett about how he’s been helping him with his golf game. And with everything back to normal, we’re ready for our first guest.

“And now to meet our first contestant, would you enter and sign in please?”

The camera cuts to a tight close up of a blackboard. There’s the sound of a few soft footsteps off camera, then an arm appears from the left holding a piece of chalk. The arm draws the words ‘MR X’ on the blackboard, drawing a circular full stop after ‘MR’ with a flourish. Daly announces ‘Mr X’ and the camera cuts to the back of the guest, a balding man in a grey suit and round glasses. He shakes hands with Daly and takes his seat to the left.

“Now for reasons that will be clear later, we are presenting our guest as Mr X, but let the folks in the theatre and the folks at home know exactly what your line is.”

The camera closes in on the mystery guest as his job appears on the screen overlaid on him. The audience applauds politely and there’s a murmur of low conversation.

“Alright panel, we can tell you Mr X is self-employed and deals with a service and we’ll begin the general questioning with, uh, Arlene Francis.”

“Mr X, are you Mr X because your name has appeared in the paper, in the last, uh, month?”

Mr X looks to Daly who purses his mouth and nods repeatedly. He turns to Francis and responds. “Yes.”

“Is it a name, probably, well known to the panel?”

Mr X nods gently. “Yes.”

“Do you have anything to do, in any way, with the arts?”

Mr X thinks for a second, then turns quickly to look at Daly. The camera pans out to include them both.

“Well I would think we would have to agree that you have something to do, in any way, with the arts, yes?” They both look back to Francis.

“Is it one of the graphic arts?”

Mr X looks back at Daly, who purses his lips.

“Mmm, no, I would say not. That’s one down and nine to go. Mr Cerf.”

Daly flips over a wooden board at the front of his desk, changing it from a question mark to ‘$5’. Mr X shakes his head in agreement. Bennett Cerf asks his first question.

“Mr X, has the work that you have been doing, and which has brought you the fame which has brought you I’m sure to this programme, go anything to do with the government?

Mr X shakes his head “No.” Daly flips over another board that says ‘$10’ “Two down and eight to go - Miss Kilgallen.”

“Ah Mr X can you conduct your work wearing an ordinary business suit?”

“Yes.”

“Do you work in the daytime?”

“Yes.”

“Do you usually work indoors?”

“Yes.”

“Uh, do you have anything to do with one of the performing arts, in some sense?”

Mr X looks at Daly again, who repeats the question, “Do you have anything to do with one of the performing arts in some sense? I’d say so, yes.” Mr X nods in agreement and says “Yes”. They both look back towards Francis.

“Would it be, uh, the theatre or the opera?”

Mr X says “No” and Daly flips over another board that says ‘$15’. “That makes it three down and seven to go - Mr Hackett.” The camera moves to Buddy Hackett, looking askance at Mr X through squinted eyes. As he asks his question his jaw chews on the words as if they were bubble gum.

“Mr X, I take that X, uh - this answer if I’m phrasing it right should be ‘yes’ - the X is not half of a name like ‘secret agent X9’ - is that right?”

The crowd erupt in laughter and the camera cuts to Mr X and Daly laughing and nodding.

“Mr X, when you go out of doors, do you wear a hat?” The laughter increases as the camera cuts to Mr X, his bald pate gleaming in the studio lights.

“Ever since Buddy adopted that Beatle wig of his there, you know…” Daly responds, and Hackett tugs his thick black forelock - “It’s real, you know! Mr X, would you like to have hair? That’s another question!” Mr X and Daly continue laughing as Hackett asks his next question.

“Do you have anything to do, er, with the new Lincoln Center?”

Another small shake of the head from Mr X - “No.” Daly flips another board showing $20. “Four down and six to go - Miss Francis.”

“Since you have ruled out the graphic arts, may I assume you have nothing to do with a drawing board, whatsoever?”

“Yes, that is correct.”

“Ah-huh. However, what you do is creative, is that correct?”

There’s a small nervous laugh in the crowd. Mr X looks at Daly, who seems equally perplexed. Daly says “We’ll have to have a small conference.” and they both lean in for a private conversation, Daly’s hands hiding their mouths from the panel. “We say no. That’s five down and five to go. We’re assuming here that you are using the word ‘creative’ in the artistic sense, and we would have to agree here that the answer should be no. Mr Cerf.”

The camera cuts to a confused looking Arlene Francis, her mouth dropped open, then pans to Bennett Cerf.

“Mr X, we did elicit from you the fact that you are somehow connected, in some way, with the performing arts, but not the theatre and not motion pictures, is that right? Might you have anything to do with television or radio?”

“Yes.”

“Would it be television?”

“Yes.”

“Uh, but you are not the representative of any government or state commission, is that correct?”

“That is correct.”

“You are self-employed. Have you got anything to do with the ratings of television channels?”

The camera cuts to Mr X, who nods and says “Yes”, and Daly, who is suppressing a grin.

“Are you Mr Nielsen?”

Daly exclaims “Yes!” and bounces up in his chair, applauding, the audience quickly following, the panel now grinning in acknowledgement.

“May I formally present Mr A.C. Nielsen Jr., who is the President of the Nielsen Service.”

Arlene Francis jokes “We have been led to believe that is creative in a way!” and everyone laughs as Daly replies “Actually, that’s why I came back and said ‘in an artistic sense’”

A nervous excitement takes over the panel as they realise the influence and power Mr X has over their television careers. “Be careful what you say you fools!” Cerf laughs nervously. Buddy Hackett rests his hand lightly on his fingers, and looks seriously at Mr X through squinted eyes.

“On behalf of Max Liebman, I’d like to say a word to you about a show I once had called ‘Stanley’…”

Hackett had been the star of Stanley, a sitcom produced by Max Liebman, for just one season in 1956-57. It was cancelled after consistently poor ratings. Mr X replies “Well, this particular show I hope gets a very high rating.” The panel and audience laugh, and Daly gestures to Dorothy Kigallen who straightens her back and speaks deliberately, as if reading from a card - “I just want to say on behalf of What’s My Line, we love Mr Nielsen.”

The panellists and host are now flattering Mr X as if he was minor royalty, Daly tripping over his words as he quickly agrees.

“We do. We love the public who makes it possible for Mr Nielsen to make it possible for us to be lovely to Mr Nielsen into the public, or something like that, how’s that for everything? I must say, it’s been a lot of fun, I, er, I didn’t think they’d catch it, but they did in fact when they got into the arts I thought anybody got into television I was afraid we’d get hooked, thanks very much, nice to have you with us.”

Mr X leans over and shakes hands with Daly, then rises and walks to the panel to shake their hands - Cerf and Hackett standing to meet him, Kilgallen and Francis remaining seated - before leaving the set to the left.

After the audience applause finishes, Daly flips the boards back to the question mark.

“Allright, now to meet our next challenger.”

For just over 8 minutes, on the evening of Sunday, Feb 16th 1964, Arthur C Nielsen Jr. stepped out in front of the audience, briefly tasting the glamour and fame of a television appearance. Although his face was anonymous, his name was well known, especially to the talent on screen, who’s careers depended on his data.

In 1964, the year The Beatles and Arthur C Nielsen Jr appeared on TV just a few hours apart, the amount spent on TV advertising in America had reached $2.28bn, second only to newspaper advertising. By 1973, it would almost double again to $4.5bn

But these billion-dollar industries were based on an incredible tiny amount of data. A 1965 CBS documentary called The Ratings Game revealed that Nielsen’s sampled data relied on just 1,130 ‘Nielsen families’ - households who agreed to have the Nielsen measurement technology installed in their homes so that their viewing patterns could be recorded and analysed.

Each one of those thousand or so Nielsen families had an economic and creative power that would have been almost impossible for them to imagine. Every decision they made to switch on the television or change the channel directly affected the commissioning decisions of the emerging TV broadcasters, the budgets of advertising campaigns for Madison Avenue advertising agencies, the rise and fall of share prices on the New York Stock Exchange, and, as Buddy Hackett had sourly noted, the careers of a new generation of TV talent. Each Nielsen family represented about 45,500 other families - about the size of a small town - and their decisions influenced around £2m of TV advertising spend. Without even knowing it, they were kingmakers, wielding power like the gods of Ancient Greece, but with buttons, dials and remote controls instead of bolts of lightning.

So how did television - the medium that more than any other defined the twentieth century - come to rely on such a small number of people for their ratings? And how did the Nielsens - father and son - end up with such a monopoly over the industry that they became a household name?

The Nielsens’ empire was built on solving a simple problem - how can you measure what people are doing when you can’t see or hear them? The technology revolutions of the 20th century created powerful communication networks - first radio and television, then later the internet - but as the power of these networks was their ability to cover great distances, they created a new problem. If you were providing a service over these networks, how could you measure your audience when they were hundreds of miles away, sitting in their living rooms?