Have we reached Peak Data?

We have never had more data about our audiences and users. Are they about to turn back into ghosts?

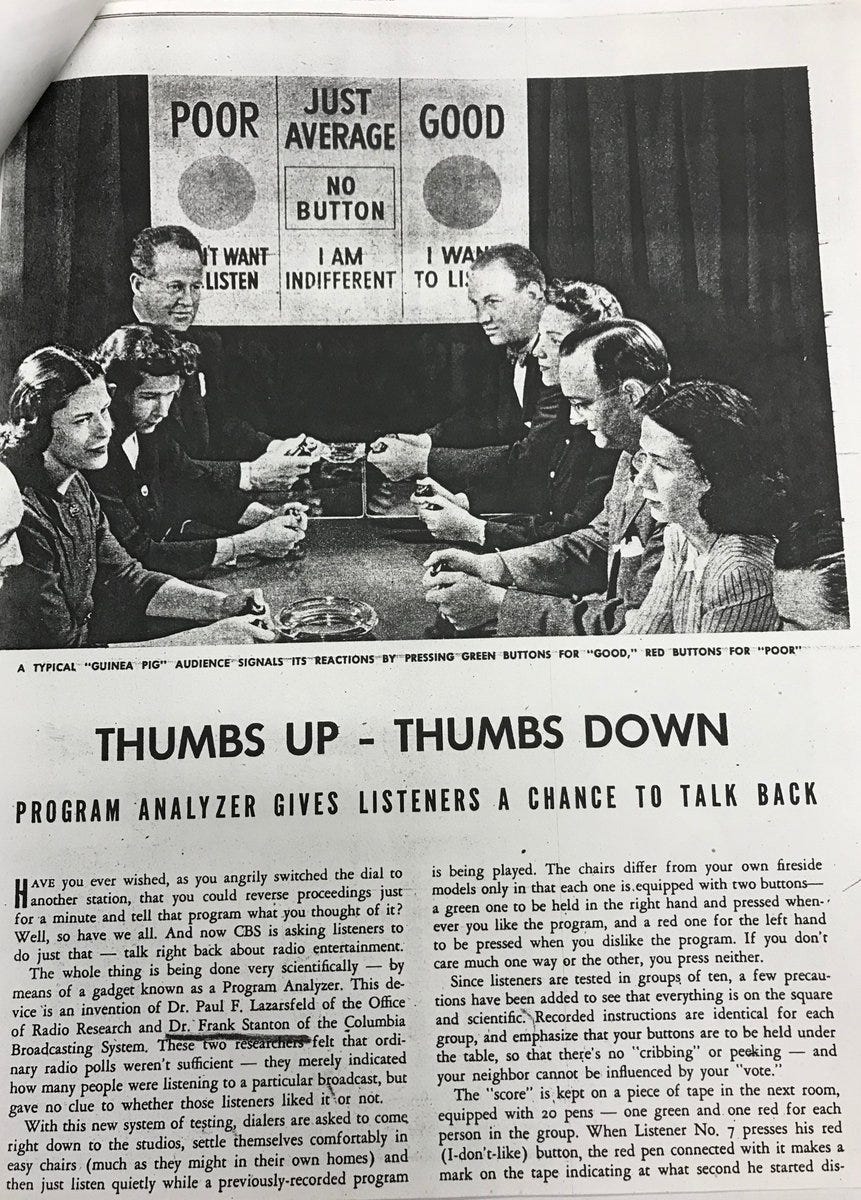

Image: CBS Program Analyser. Credit: @joshshepperd h/t to Nathan Martin for the link!

This might be the most interesting time to start a newsletter about the history of audience measurement.

And I mean interesting in the spirit of the apocryphal Chinese proverb ‘may you live in interesting times’. Because we might be at the end of a one hundred year journey to measure the invisible audiences at the end of technological broadcast networks.

In the early twentieth century, the invention of radio broadcast networks (and the telephone services that preceded them) created a fascinating new problem for cultural entrepreneurs - how do you measure invisible audiences? If you don’t have a tangible connection with them, through ticket sales, or by being in the same room as them, how can you tell how many people are listening or viewing?

The last 100 years have been a journey to see how to measure ghosts - how to measure the invisible audiences at the end of technological distribution networks. With every decade, these ghosts have come more and more into focus, ending with a the last ten years of social media and digital advertising that has created unimaginable amounts of data about everything we see, read, click and like.

The globe-spanning empires of radio, TV, music, film and digital media have grown by feeding on this data, and developing metrics that have turned this data into cold, hard cash. Or, if you’re in the arts, annual reports, which in turn mean your funders keep giving you cold, hard cash.

If you’ve subscribed to this newsletter, the chances are that you work in one of these industries. At some point, you have had to use this data to work out whether the things you commission or make are actually any good. You probably hated doing this. It involved spreadsheets, or questionnaires, or a presentation full of badly drawn charts. There would have been jargon involved, like MAUs, or conversion funnels, or ratings, or appreciation indexes.

But underneath the numbing surfaces of those spreadsheets and reports there is a strange history, full of ideas, innovators, politics and power. Every new way of distributing culture has had to develop new ways of measuring audiences. Without metrics, they couldn’t convert attention into money, and without money, they couldn’t grow into billion-dollar global empires.

There are some fascinating stories hidden in the history of audience metrics. Let’s go and find them.

Why Apple’s new login means we might have reached Peak Data

It may be ill-advised, but I’m currently re-watching the entire series of Lost with my teenage daughter. I know we’re going to end up frustrated in the end, but we’re only on Season One at the moment, and one of the things I’ve remembered Lost did so brilliantly was jumping across timelines, moving from the back stories of the characters to their present lives on the island with that ominous wooshing noise.

Like Lost, this newsletter is going to jump across timelines. I’ve spent the last decade or so researching the history of audience metrics, and this newsletter was started partly to help me continue this research. In every newsletter, I’m going to try and provide a mix of historical research and commentary on what’s happening right now. Also like Lost, I don’t yet know where this is going to end up. Apologies.

This week, I want to talk about Apple’s new sign-in service, announced at this week’s WWDC. At one level, you can read this as just the latest attempt by the major platforms to create lock-in for their ecosystems (and if you’re interested in exploring this more, you’d be interested in my other project, the Public Media Stack). Apple is going to force every app developer who currently uses Facebook or Google for sign-in to also offer the new Apple service. This is a shot across the bows of their ecosystem rivals, and will potentially deprive Facebook and Google of tons of valuable audience data.

But the really interesting thing is the announcement that they’re developing the service with a ‘minimum viable data’ strategy. The sign in service will create a unique email address for every service you sign in to, making it almost impossible to track users across services - one of the most important goals of digital ad-serving networks. If you want to stop using a service for ever, Apple will delete the link between the one-time email address they created and your real iCloud email address, which will make it impossible for a service to reconnect with you.

This is the latest part of Apple’s ‘Privacy Matters’ campaign, positioning themselves as the anti-Facebook/Google. They’re pushing hard on their pro-privacy policies at the moment, and clearly feel that this gives them a competitive advantage, especially over competitors who are facing anti-trust proceedings in the US driven mainly because of their exploitation of user data.

So is this a sign we’ve reached Peak Data? After one hundred years of slowly measuring audiences through sampled ratings and surveys, then 15 years of exponential growth of ‘big data’, are we finally reaching the point where the tide turns, and ‘just enough’ strategies replace ‘just in case’?

Well, maybe. But only for a privileged few. If there’s one constant in the economics of audience data over the last 100 years, is that we only get free services if we pay for them with our attention. This has been true for commercial radio and television, free newspapers, mobile games and digital content. If we want privacy, we have to pay for it, and not everyone can afford this. Will the right to become a ghost only be for the people with money to buy premium products?

Back in 2004, my innovation team at the BBC produced a number of scenarios about how children might use the internet in 2014. There’s a lot they got right, but the three scenarios all imagined a mixture of more controlled commercial networks in which privacy and security were strong, and deregulated open networks where risks were higher and users were monetised via their data.

This feels like the direction we’re going in now - after a decade of having our data strip-mined by the big ecosystems, we’re going to see the growth of services moving in the opposite direction, offering more privacy and less tracking. But only if you have the means to pay for it. This is worrying, because, as we found in researching those scenarios, it’s often the people who most need security and privacy who can’t afford to pay for it - children, refugees and immigrants, people in low-income households or with precarious support networks.

From a commercial perspective, there is a very real danger that your most financially secure customers will become increasingly invisible to you, and you’ll have to find new ways to develop a relationship with them. But more worrying to me is that people who can’t afford to pay for privacy will be increasingly giving up their data in return for services that they need to get by in our digital age. We might have reached peak data, but perhaps only for the well-off.

Thanks for reading this first newsletter, and I hope you’ve found it useful. It’s ironic that I’m writing this to an audience of ghosts - I recognise some of the 100 or so of you who have signed up for this first newsletter, but I’d love to know more about you all.

Do you think we’re reaching Peak Data? Are we going to see a split in how richer and poorer audiences’ attention is measured? Is there a specific issue or subject related to audience data that you’d like me to talk about? Have you got any of your own insights or research that you’d like to share?

Please get in touch by replying, or commenting on the web version of this newsletter by clicking the button below. And please do forward this email to anyone you think might be interested - I’d love to build a big and vibrant community around this fascinating subject, so please invite anyone else to join us. Thanks!

Matt