'A Dictatorship of Numbers'

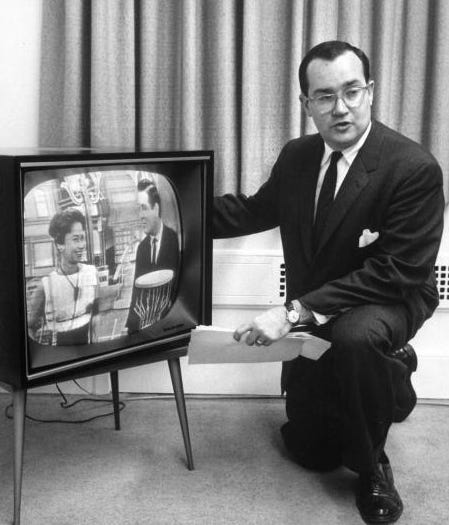

Newton Minow's 1961 'vast wasteland' speech paved the way for public media in the US. We need another Newton Minow now.

On May 9th, 1961, Newton Minow stepped up to give a speech to the National Association of Broadcasters at the Sheraton Hotel in Washington DC. Just a few months earlier, Minow had been appointed Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, the organisation that regulated the US broadcasting industry, by President John F. Kennedy. Minow and JFK shared a vision for how television could impact society, worried about how their own children were spending so much time watching TV, and so when Kennedy was voted President, Minow asked if he could be appointed to the FCC.

The day before Minow gave his speech, Kennedy had spoken to the same audience. He was only a few months into his presidency, developing his vision of a US standing at the beginning of a ‘New Frontier’ - facing the challenges of communism and post-war political upheaval, but also the opportunities of new technologies and the space race. In his speech, President Kennedy told the audience of broadcast executives about his political vision for America, and how the new communications technologies they controlled would serve the fight for freedom against despotic rivals:

“…if we are once again to preserve our civilisation against our enemies, it will because of our freedom, and not in spite of it. This is why I am here to day with this most important group. For the flow of ideas - the capacity to make informed choices - the ability to criticise - all the assumptions upon which political democracy rests - depend largely on communication. And you are the guardians of the most powerful and effective means of communication ever designed. In the rest of the world this power can be used to describe the realities of communist despotism - and to give a true and responsible picture of our free society.

[…] And here, in our own country, your power is used to tell our people of the perils and challenges we face - of the effort and painful choices which the coming years will demand. For the history of this nation is a tribute to the ability of an informed citizenry to make the right choices in response to danger. And if you play your part - if the immense powers of broadcasting are used to illuminate the new and subtle problems which our nation faces - if your strength is used to reinforce the great strengths which freedom brings - then I am confident that our people and our nation will once again his to the occasion.”

Television was coming to the end of its first Golden Era, as American families adopted the new technology in record numbers, and advertisers flocked to the new networks. Regular network broadcasts only started 14 years earlier, in 1947, when there were 44,000 TV sets in US homes, around 30,000 of them in New York. By 1960, there were 52 million, one in almost nine out of ten households.

That rapid growth had led to problems. In the late 1950s, the TV industry was rocked by a series of quiz show scandals, as producers chased ratings by slipping answers to popular contestants. The FCC had introduced new regulations in response, and as the leaders of the US broadcast industry waited in the ballroom of the Sheraton hotel for Minow’s speech, they were anxious to hear what the new FCC Chairman was going to do next.

Minow went much further than even the most pessimistic broadcast exec could have expected. He started by reassuring them of his knowledge of the sector, reeling off a list of stats about how successful and profitable the networks were, but also recognising the anxiety they might have about his role:

“It wouldn't surprise me if some of you had expected me to come here today and say to you in effect, "Clean up your own house or the government will do it for you." Well, in a limited sense, you would be right because I've just said it.”

But Minow didn’t see his role as that of a teacher punishing a naughty classroom. He didn’t want to just issue a slap on the wrist, but to do something much more revolutionary.

For him, the problem with the emerging TV sector was not a lapse of morals about running quiz shows, but something much deeper - it lacked a vision for the public interest potential of this new medium. In his speech, Minow linked the need for a public interest vision to the ‘new frontier’ vision JFK had articulated the night before:

“Your industry possesses the most powerful voice in America. It has an inescapable duty to make that voice ring with intelligence and with leadership. In a few years, this exciting industry has grown from a novelty to an instrument of overwhelming impact on the American people. It should be making ready for the kind of leadership that newspapers and magazines assumed years ago, to make our people aware of their world.

Ours has been called the jet age, the atomic age, the space age. It is also, I submit, the television age. And just as history will decide whether the leaders of today's world employed the atom to destroy the world or rebuild it for mankind's benefit, so will history decide whether today's broadcasters employed their powerful voice to enrich the people or to debase them.”

For Minow, the landscape of television in 1961 was a long way from achieving this vision. He noted that in the networks’ schedules for the next season, amongst 73 hours of prime-time viewing, 59 hours were dedicated to sitcoms, quiz shows, action dramas or movies. This was the ‘vast wasteland’ that he wanted broadcasters to change:

“[…] when television is bad, nothing is worse. I invite each of you to sit down in front of your television set when your station goes on the air and stay there, for a day, without a book, without a magazine, without a newspaper, without a profit and loss sheet or a rating book to distract you. Keep your eyes glued to that set until the station signs off. I can assure you that what you will observe is a vast wasteland.

You will see a procession of game shows, formula comedies about totally unbelievable families, blood and thunder, mayhem, violence, sadism, murder, western bad men, western good men, private eyes, gangsters, more violence, and cartoons.

And endlessly, commercials -- many screaming, cajoling, and offending.

And most of all, boredom. True, you'll see a few things you will enjoy. But they will be very, very few. And if you think I exaggerate, I only ask you to try it.”

Minow asked the broadcast execs why so much of television was so bad. Was it pressure from the advertisers? The need for higher ratings and mass audiences? He didn’t believe the usual answer that ‘this is what the public wants’ - for Minow, the public interest was not just ‘what the public were interested in’. He had a keen knowledge of how TV ratings were captured, and challenged the broadcast execs to ask themselves whether ratings were a true measure of what the audience really wanted to watch:

“I do not accept the idea that the present over-all programming is aimed accurately at the public taste. The ratings tell us only that some people have their television sets turned on and of that number, so many are tuned to one channel and so many to another. They don't tell us what the public might watch if they were offered half-a-dozen additional choices. A rating, at best, is an indication of how many people saw what you gave them. Unfortunately, it does not reveal the depth of the penetration, or the intensity of reaction, and it never reveals what the acceptance would have been if what you gave them had been better -- if all the forces of art and creativity and daring and imagination had been unleashed. I believe in the people's good sense and good taste, and I am not convinced that the people's taste is as low as some of you assume.

[…]

You must provide a wider range of choices, more diversity, more alternatives. It is not enough to cater to the nation's whims; you must also serve the nation's needs. And I would add this: that if some of you persist in a relentless search for the highest rating and the lowest common denominator, you may very well lose your audience. Because, to paraphrase a great American who was recently my law partner, the people are wise, wiser than some of the broadcasters -- and politicians -- think.”

This was not just an airy vision - Minow then set out six principles that would guide his Chairmanship of the FCC, starting with the principle that the people own the airwaves, not the broadcasters, but also vowing to keep government censorship out of broadcast networks, and to stop fighting the still raw battles around the quiz show and payola scandals. And he went on to announce initiatives that he had already started to approve - an early experiment with pay TV, the opening up of UHF spectrum to allow more broadcast networks.

Unlike President Kennedy’s high political rhetoric the night before, Minow delivered not just a vision, but a clear plan of action. He was not asking for permission from the broadcasters, but challenging them to come on the journey with him.

Although his Chairmanship of the FCC only lasted a little over two years, his vision fundamentally changed the ‘vast wasteland’ of commercial broadcasting, and paved the way for public media in the US. He ensured that the new UHF spectrum would carry with it a requirement for educational programming, paving the way for the 1967 Public Broadcasting Act that created the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and later PBS and NPR. Without Minow’s vision, there would be no Sesame Street, Frontline, Nova or This American Life. Public broadcasting in the US might seem tiny compared to the BBC and other public-funded broadcasters around the world, but without Minow, the US wouldn’t have anything at all.

We are almost exactly sixty years on from Minow’s speech, and we are at another inflection point for a new communications technology. We might not have the youthful optimism of JFK’s ‘new frontier’, but we are at a similar moment of rapid change, at the end of the first golden era of another global network. Television broadcast networks were only 14 years old in 1961 - social networks like Facebook and Twitter today are also still in their unruly teens. Anyone challenged to spend a day scrolling through their social feeds will find a ‘vast wasteland’ even more problematic than the one Minow saw on his television screen.

The last couple of years have seen a growing conversation about what we can do to change that vast wasteland, including breaking up the monopolistic tech companies, lobbying advertisers to stop funding bad actors, and many initiatives to invest in technology that starts with a public interest vision rather than commercial gain.

And finally, after years of growing pressure, the platforms themselves have started realising they are responsible for some of the content they host on their platforms. Banning the President of the United States of America from your platform is an unprecedented step, a crisis far more serious than the payola and quiz show scandals that TV faced in the late 1950s.

What we don’t have, and sorely need, is a vision from a leader like Minow of a better alternative, tied to a practical programme of change, and the political power to make it happen. The monopolistic technology platforms are deeply immersed in our everyday lives, as intractable as milk in tea. It feels impossible to imagine what a better version of them could look like. Many of us mourn the early optimism of the social web, but we can’t rewind time and try again.

What Minow did was not just identify the problem, but demonstrate a deep knowledge of the economic and technical issues facing the industry, and articulate a vision for how to make it better. He didn’t just criticise, but challenged his audience to stop hiding behind commercial arguments for the status quo, and start serving the public interest. Towards the end of his speech, Minow referred back to an earlier quote from Governor Collins, the President of the National Association of Broadcasters, about the need for broadcasters to serve the public interest despite the pressures of advertisers:

“I join Governor Collins in his views so well expressed to the advertisers who use the public air. I urge the networks to join him and undertake a very special mission on behalf of this industry. You can tell your advertisers, "This is the high quality we are going to serve -- take it or other people will. If you think you can find a better place to move automobiles, cigarettes, and soap, then go ahead and try." Tell your sponsors to be less concerned with costs per thousand and more concerned with understanding per millions. And remind your stockholders that an investment in broadcasting is buying a share in public responsibility. The networks can start this industry on the road to freedom from the dictatorship of numbers.”

We are living through the consequences of another ‘dictatorship of numbers’ right now. We thought the social web would lead to a ‘new frontier’ of progressive change and freedom, but instead we have monopolistic platforms run by algorithms that sell our attention and emotions to advertisers.

We need a bold vision for how we can change this - not a mournful paean to the failed dreams of 14 years ago, but something that ties a new vision of public value in the digital age to a practical plan for the projects, institutions, networks and regulations that can make it happen. This needs to come not just from activists and campaigners, but from someone, like Minow, with the power to bring it to life.

Like JFK in 1961, we’re about to see a new President in the United States, and a new set of appointments to the institutions that run public life. I hope at least one of them is a new Newton Minow.